The Greasy Grass : Touring Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

Philip Aggio • July 29, 2025

Like a ragged scar on the landscape, the bluffs rise above the trees that grow by the river that has flowed through this grassland since the distant past. In an awkward juxtaposition, the landscape is broken by a ribbon of asphalt. The sounds of nature have been replaced by the steady drone of traffic on Interstate 90. On the top of one of the bluffs stands a large marble obelisk, that provokes the question, “What happened here?”

This is the story of one of America’s most iconic—and misunderstood—battles, set in the rolling grasslands of Montana. Today, we take a tour through the echoes of that day, beginning with our arrival…

Stop 1: Arriving at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

While it’s possible to visit Little Bighorn with your RV, it’s not ideal. Battlefield Road is narrow, and the parking lots cannot accommodate large recreational vehicles. For the best experience stay just outside the battlefield at 7th Ranch RV Park.

This private RV park is nestled right next to the national monument. It’s located on what was the southern edge of the Native American village led by Sitting Bull. It was this end of the village that came under attack by Major Reno. You will be literally staying in the middle of history. 7th Ranch RV Park offers spacious sites, discounts for Good Sam and Escapees members, and when we stayed here, free ice cream at check in. It’s the ideal place to setup camp and relax after a long travel day. It’s also the only RV park in the area. Stay a couple nights you will have the time to explore the national monument more thoroughly.

A short distance east from exit 510 on Interstate 90, there is an inauspicious road on the right-hand side of U.S. Highway 212. It is marked with a large brown sign that reads Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. This is Battlefield Road. A four a half mile winding drive that connects the two battlefields that comprise the national monument.

Following Battlefield Road, beyond the trees that shade the national cemetery and the visitor center, a large obelisk comes into view on the right side. It stands on top of a little knoll making it visible from the interstate. This is Last Stand Hill, the place where the bodies of Custer and his men were found. It may be the first stop on the tour, but they fell in the last stage of the battle and not the beginning.

To retrace the steps of the doomed men of the 7th Calvary we need to start four and half miles away at a place now called the Reno-Benteen Battlefield. In truth, it is necessary to travel almost a thousand miles to the southeast and almost one and sixty years into the past to find the origins of the battle.

Visitor Tips for Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

Planning your visit? Here are some helpful tips to make the most of your time:

- Best Time to Visit: Late spring to early fall offers the best weather and clearest views of the sweeping battlefield.

- Hours & Entry: Open year-round (except some federal holidays). Entry fees vary, check the NPS website for current rates and seasonal hours.

- RV Parking: RVs are not recommended inside the monument due to narrow roads and small parking lots. Stay nearby at 7th Ranch RV Park, which offers big rig-friendly spots and a convenient location.

- Restrooms: Available at the visitor center and cemetery.

- Interpretive Programs: Ranger talks and walking tours available seasonally, check the daily schedule posted at the visitor center.

- Audio Tour Option: Pick up the self-guided battlefield driving tour CD/USB at the visitor center gift shop or download the NPS app for a GPS-guided tour.

- Maps & Brochures: Free battlefield maps are available at the visitor center. You can also download one below.

- Cell Signal: Cell service is limited in some areas. Download maps, directions, and audio before arriving.

Stop 2: Custer's Luck

George Armstrong Custer graduated last in his class from West Point in 1861. During the Civil War his abilities as a calvary commander were recognized and he rapidly rose through the ranks. At Gettysburg, Custer successfully held off Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Calvary. It was a success that was a decisive part of the Union victory. That success came at a very steep price. He had lost 257 men, the highest loss of any brigade in the Union Calvary.

At the age of 25 Custer would again make history when on April 15, 1865, he was promoted to Major General in the U.S. Volunteers. He was the youngest general in the Union Army.

Custer was appointed Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army and placed in command of the newly formed 7th Calvary on July 28, 1866. In 1867 he was arrested for being AWOL and suspended from the army for one year. Before that suspension was up, he was returned to active duty at the request of Major General Philip Sheridan. Sheridan wanted Custer to be part of the planned winter campaign against the Southern Cheyenne.

The Washita: Prelude to Controversy

On the icy morning of November 27, 1868, Custer and the 7th Cavalry launched a surprise attack on a Southern Cheyenne village along the Washita River, near present-day Cheyenne, Oklahoma. In the darkness before dawn, the stillness was shattered by the cavalry musicians playing “Garryowen”—a signature of the 7th—and the sudden burst of gunfire.

“We heard a woman saying in a low voice: 'Wake up! White men! White men are here! The soldiers are approaching the camp.' We became frightened, and did not know what to do. We arose at once. At that instant, the soldiers let out terrible yells, and there was a burst of gunfire from them...” Moving Behind

Custer's strategy was clear: capture women, children, and elders to force Native warriors into submission and guarantee a safe retreat. The Southern Cheyenne numbered around 250; Custer brought 574 men.

“For this reason, I decided to locate our camp as close as convenient to the village… exposure of their women and children… would operate as a powerful argument in favor of peace.” – George Armstrong Custer

But things didn’t go entirely to plan.

During the chaos, Major Joel Elliott, who had led the 7th during Custer’s earlier suspension, broke off with a detachment to chase fleeing warriors, yelling, “Here’s for a brevet or a coffin!” They rode directly into a large force from neighboring villages—villages Custer’s scouts had either missed or ignored. Elliott and his men were never seen again. Custer withdrew from the area without confirming their fate and later declared victory.

Official reports exaggerated the success. The 7th Cavalry lost 21 men and 13 were wounded; estimates suggest the Cheyenne lost about 50, with similar numbers wounded.

Nearly a month later, Custer returned to the battlefield with General Sheridan and 1,700 troops. They found Elliott’s detachment, frozen and brutally mutilated. The sight left deep resentment in the ranks, especially among those loyal to Elliott, including Captain Frederick Benteen.

That resentment toward Custer never faded. And when the 7th Cavalry rode into the Battle of Little Bighorn eight years later, it rode in with those old wounds still open.

Soldiers Falling: The Road to Little Bighorn

Crow Agency, Montana; is one of those places that if you blink, you’ll miss it. To the Crows, this is home. The Crows have always lived here, and they were mortal enemies of the Lakota and North Cheyenne tribes. It was for this exact reason that Sitting Bull brought his large gathering of “hostile” bands here. It was the last place the U.S. army would look for them.

They didn’t have permission to be there. But Sitting Bull wasn’t seeking permission—he was defending a way of life. The Crows, seeing their ancestral lands overrun, allied with the U.S. Army to drive out the intruders.

Determined to maintain their traditional way of life, Sitting Bull with the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne, who had refused to accept government rations and move onto the reservations, had gathered for one last great hunt on their ancestral hunting grounds. Their refusal to submit to the government’s demands had not gone unnoticed. The U.S. Army was looking for them, with orders to subdue and bring them into the reservations.

Just a couple of weeks before the infamous battle, near present-day Lame Deer, Montana, the tribes held their annual Sun Dance. During the ceremony, Sitting Bull received a powerful vision:

“Soldiers falling into his camp like grasshoppers from the sky.”

It was a sign. He believed a great victory was near.

Into The Field

The Army’s plan was bold—trap the “hostiles” in a massive pincer movement.

- General Crook would march from the south.

- Colonel Gibbon from the west.

- And Custer from the east.

They believed there’d be no escape. The tribes would be cornered and forced onto reservations.

But things began to unravel before the campaign even launched.

In May 1876, Custer was arrested after leaving Washington without President Grant’s permission. He had just testified before Congress, calling out corruption in the Indian Affairs Office. Grant, furious, tried to have him removed from the campaign entirely.

Public backlash was immediate. Newspapers tore into the President for punishing a national hero. Under pressure, Grant compromised: General Terry would officially lead the campaign, but Custer would still command the 7th Calvary.

There were rumors that the whole incident had been politically motivated. Custer was a Democrat and there was talk that he was going to be the party’s nominee for president in the next election. President Grant, a Republican, may have been trying to take out a future political rival.

“The 7th can handle anything it meets”

Chaffing under the restrictions placed on him, Custer was eager to take to the field with his 7th Calvary. The chance finally came on June 22, 1876, when Custer and the 7th Calvary were cut loose from Terry’s column. They were to follow up on a discovery made by Major Reno on a previous scout. On June 15 Reno had found the trail of a large Native American village on the Rosebud. Custer and the 7th Calvary wasted no time in following it. All were certain that victory and glory would soon be theirs.

On the evening of June 24, 1876, Custer’s scouts showed him the “hostiles” village. They were at a lookout known today as “The Crow’s Nest” in the Wolf Mountains, about 14 miles East of the Little Bighorn River. It was the largest Native American Village they had ever seen. Undeterred by its size, Custer made plans to attack it at dawn on June 26.

Splitting the 7th Calvary

Concerned that the “hostiles” would scatter. That night Custer divided the 7th into 3 commands. Captain Benteen with 3 companies would scout to the southwest and “pitch into anything” they found. Major Reno with 3 companies would head up the valley to attack the village. Reno’s instructions were “pitch into what was ahead” with the assurance that he would “be supported by the whole outfit.” Reno’s attack would draw whatever warriors that were in the village out to face the enemy. Custer would keep 5 companies with him. The slow-moving pack train, carrying ammo and supplies, would follow behind. Custer would flank the village and charge it from the North. Their goal would be to capture as many women, children and the elderly as possible. They would use these captured “non-combatants” to force the warriors to concede to their demands and surrender. Unfortunately, and maybe even unknown to Custer, neither Benteen nor Reno were fit to command.

Benteen was bitter and resentful about his commanding officer. This has been attributed to Custer’s decision to withdraw from the Washita, without determining the fate of Major Joel Elliot and his men.

Major Reno was still grieving the death of his wife Mary. She had passed away in 1874. Since her passing he was dealing with what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the 1870s this was undetected and untreated. Major Reno would later admit that his strange actions on the battlefield were due to drinking.

Stop 3: Reno-Benteen Battlefield: The Crow's Nest

Follow battlefield road for four and half miles to the Reno-Benteen Battlefield. Start your tour by locating the notch in the Wolf Mountains to the southeast. This is the Crow’s Nest. The lookout from where Custer was shown the largest village his scouts had ever seen.

There is some dispute about the exact size of the village. It is believed that there were approximately 7000 people in the village. The warriors numbered 1500-2000. It believed to be the largest Native American Village ever seen on the great plains. The 7th Calvary had just 700 troopers and scouts.

They marched all night, following the path the village had taken. On the morning of June 25, Custer received word from his scouts that their presence may have been detected. He would have to attack now.

His presence in the Wolf mountains had indeed been detected. In the village no one was overly worried.

“I did not think anyone would come and attack us so strong as we were.” — Low Dog, Oglala Lakota

Stop 4: Reno-Benteen Battlefield: Reno-Benteen Monument Entrenchment Trail

The interpretive signs that are in this area detail Reno’s attack on the southern end of the village. Its failure and the retreat to Reno Hill where the battered remnants of Reno’s 3 companies dug in.

In response to Reno’s advance, warriors surged to the southern end of the village, pushing back his companies with overwhelming force. The attack faltered. With battle lines collapsing, Reno’s troops began retreating to what is now called Reno Hill.

From a vantage point on the bluffs above, Custer had a clear view, he could see the true size of the village and witness Reno’s failed charge. It was now or never. Determined to seize the moment, Custer acted.

He sent a message by trumpeter John Martin to Captain Benteen:

“Benteen. Come on. Big village. Be quick. Bring packs.

P.S. Bring packs.”

Martin was the last man to see Custer alive.

What happened next remains uncertain, lost in the dust and chaos of the battlefield.

Stop 5: Reno-Benteen Battlefield: Weir Point

Leaving the Entrenchment trail and heading north on Battlefield Road will bring you to the next point of interest on the tour of the battlefield. It is a high promontory now called Weir Point.

Alarmed by the gunfire downstream, Captain Thomas Weir took his Company D and some of the other troops as far north to what is now called Weir’s Point. They saw clouds of dust and gun smoke covering what is now Custer Battlefield. The approach from that direction of numerous warriors forced Captain Weir and the troops to withdraw back to Reno Hill.

For the rest of the day Benteen would hold off charge after charge from the warriors. Until evening came and the battle at long last came to an end. Under cover of darkness the village broke camp and fled for safety. Over the next couple of days, the village broke up as the various bands of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne scattered in different directions.

“We fled all night, following the Greasy Grass. My two younger brothers and I rode in a pony-drag, and my mother put some young pups in with us. They were always trying to crawl out and I was always putting them back in, so I didn't sleep much.” Black Elk, Oglala Lakota

The day after the battle, June 26, reinforcements arrived to relieve the broken and battered remnants of the 7th Calvary. They found the bodies of Custer and the five companies that were with him. They were naked, mutilated and strewn around near the top of what is now called Last Stand Hill

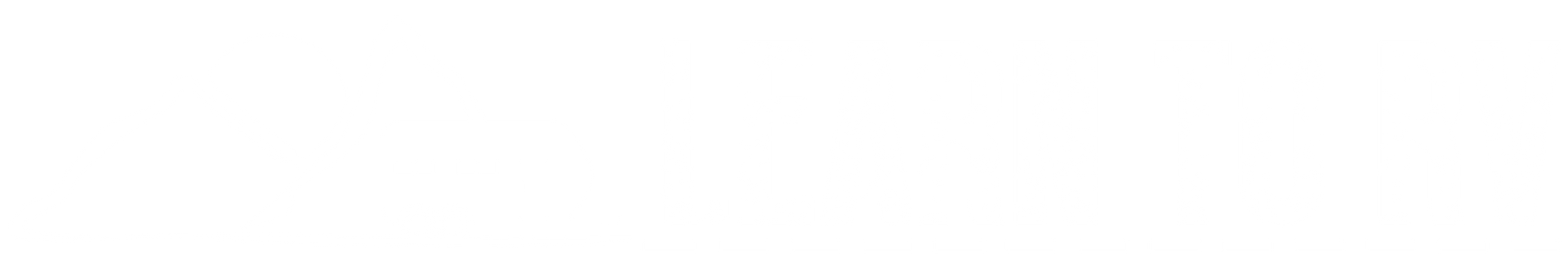

Stop 6: Medicine Tail Coulee

What really happened after trumpeter John Martin galloped away with Custer’s final message remains a mystery. No one survived from the five companies under Custer’s direct command to tell the tale.

What we do know:

It was a scorching summer day, with temperatures nearing 100°F. The men of the 7th Cavalry were exhausted, having marched through the night. As Custer moved north along the bluffs, he dismissed all of his Native American scouts—a fateful decision that left him without cultural insight or translation.

Yet the warnings were clear.

“General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of.” — Mitch Boyer

“You and I are going home today by a road we do not know.” — Yellow Face, through Boyer

Eyewitness Accounts: The Final Moments

From the opposing side of the river, Native warriors recounted what they saw:

“Soldiers came down to the ford led by one with mustache and a buckskin jacket on sorrel with a blazed face and four white stockings. On one side of him was a soldier carrying a flag.” — White Cow Bull

“They made a dash to get across, but was met by such a tremendous fire.” — Horned Horse

“Try to stop and turn them. If they get in camp, they will kill many women.” — Bobtail Horse

“Our young men rained lead across the river.” — Sitting Bull

Then came the moment that may have turned the tide:

“The man in the buckskin seemed to be the leader... I aimed my repeater at him and fired. I saw him fall out of his saddle and hit the water. Shooting that man stopped the soldiers from charging... Some of them got off their horses in the ford and seemed to be dragging him out of the water.” — White Cow Bull

Even Custer’s Crow scouts—White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead, and Hairy Moccasin—later confirmed:

“We saw Custer’s fall at the river.”

The Battlefield Aftermath

In the weeks that followed, both Major Reno and Captain Benteen conducted surveys of the battlefield. Their observations help paint a clearer picture of the chaos that unfolded.

“He moved rapidly down the river for three miles to the ford, at which he attempted to cross into their village... expecting to go with ease through the village, he rode into an ambuscade.” — Major Reno

“I went over the battlefield carefully with a view to determine how the battle was fought... I arrived at the conclusion... that it was a rout, a panic, until the last man was killed. That there was no line formed on the battlefield.

You can take a handful of corn and scatter it over the floor and make just such lines. There were none.

The only approach to a line was where five or six horses were found at equal distances, like skirmishers. Ahead of those horses were five or six men—riders who had jumped off, all heading toward where Custer was.

There were more than 20 killed to the right... four or five in one place, all within a space of 20 to 30 yards. That was the condition all over the field.” — Captain Benteen

Stop 7: Custer Battlefield: Calhoun Hill, Last Stand Hill and Deep Ravine

There is a lot to see in this area. After Custer’s attack on the village was thwarted by small group of warriors lying in ambush behind a small rise on the East side of the river. Custer’s five companies retreated first to Calhoun Hill. They were then pushed north to Last Stand Hill where they put up a fierce fight. They were finally overwhelmed, and the remaining survivors appear to have fled in the direction of a place now called Deep Ravine. It appears they never reached it. Be sure to take time to walk the trail that leads to Deep Ravine.

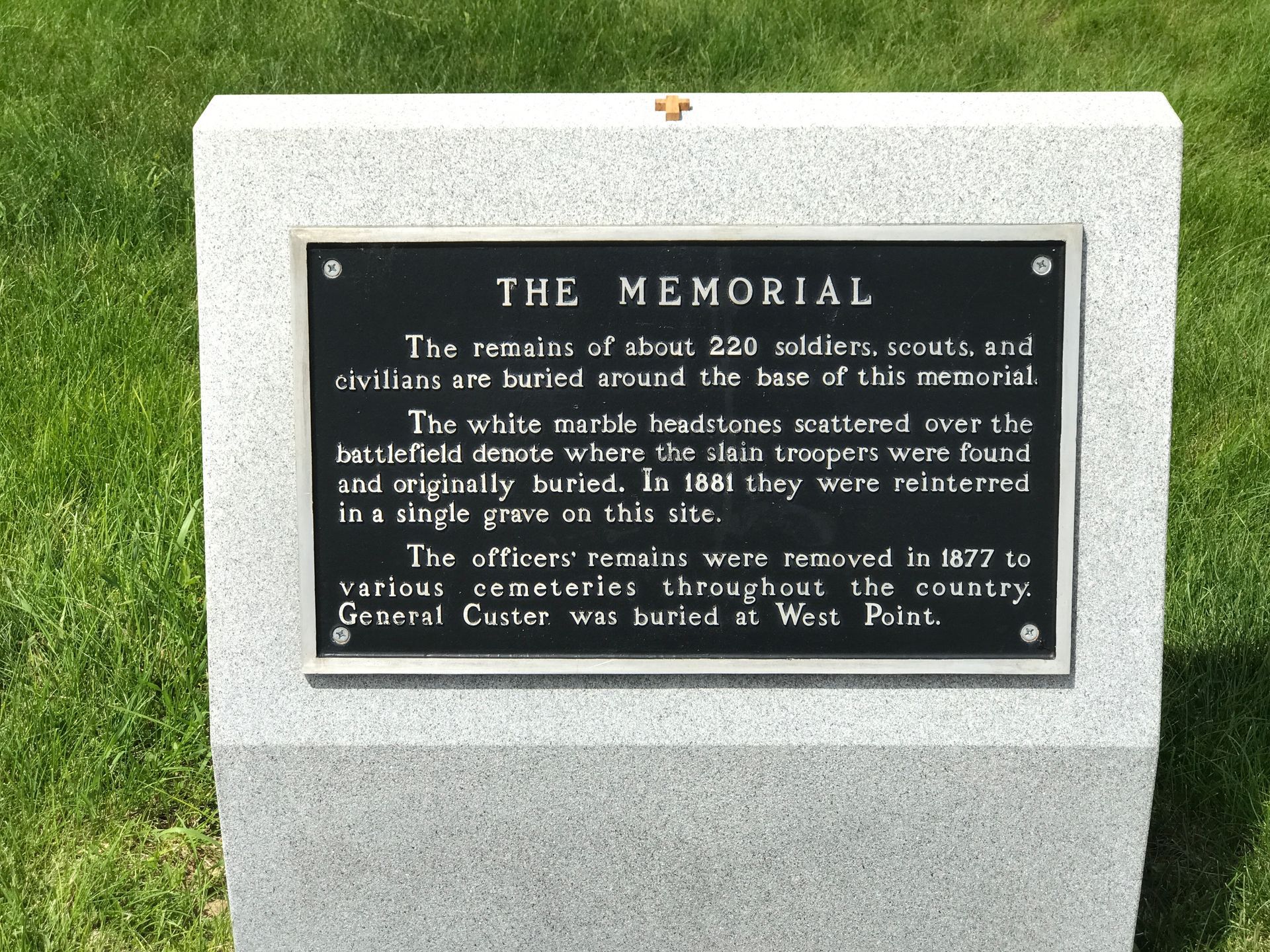

Beneath the Soldiers Monument on Last Stand hill is the mass grave where many of the fallen troopers were buried. This is their last resting placing. Of the 700 troopers that comprised the 7th Calvary, 268 were killed during the battle. 55 were wounded, 6 of these later died.

Opposite the marble obelisk, on the other side of Battlefield Road, is the Native American Memorial. It is designed in a semi-circle with the opening at its southern end. It honors the Native American Warriors who fought and died here for their way of life. 31 warriors were killed and up to 160 were wounded. There were 10 non-combatants killed.

Not all the fallen are interred in the mass grave on Last Stand Hill. Some troopers were interred nearby at the Little Bighorn National Cemetery. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer is interred at West Point. Make sure your visit has time for exploring the national cemetery. It is an important part of the story of the battle.

The Ghost Dance

It all began with the Ghost Dance—a slow, silent shuffle to a single drumbeat.

A Paiute shaman named Wovoka had a vision: the Ghost Dance would return everything to what it once was. The whites would vanish. The buffalo would return. The spirits of the ancestors would walk the Earth once more. Together, they would live again—in peace.

On December 19, 1890, the 7th Cavalry surrounded a large group of Lakota and brought them to Wounded Knee Creek. Among them were Hunkpapas from Sitting Bull’s band, who had fled after his death during a botched arrest just days earlier.

The dawn of December 20 was cold and still. The quiet of that winter morning shattered by a scuffle—and a single gunshot.

“A scuffle occurred between one deaf warrior who had a rifle in his hand and two soldiers. The rifle was discharged and a battle occurred—not only the warriors but the sick Chief Spotted Elk, and a large number of women and children who tried to escape by running and scattering over the prairie were hunted down and killed.”

— General Nelson Miles

Now, 135 years have passed since that morning. Wounded Knee marked the final chapter in the long war to subdue the tribes of the Great Plains. It remains one of the darkest pages in American history. Those who fought the war are long gone—but the questions, and the scars, remain.

Echoes on the Plains

Little Bighorn is the most well-known and remembered battle of that war. It is a place of reflection. A landscape forever marked by the violent clash of two worlds. It is hallowed ground—the final resting place of those who fell here.

The sun hangs low in the western sky. The voices of the past begin to fade, becoming echoes across the gulf of time.

At the top of Last Stand Hill, the golden rays of sunset strike the marble obelisk, a monument to the troopers who died here. Across from it stands the Spirit Gate, the open end of the semi-circle at the Native American memorial. It is designed to allow the spirits of the fallen troopers to pass into the afterlife.

And perhaps, after the visitors have gone, after the sun slips below the horizon, and the river below glows in the moonlight, there is another Ghost Dance.

Troopers and warriors, arm in arm.

Asking only for the chance to live again, in peace and unity.

“Forty years ago I fought Custer till all were dead. I was then the enemy of the white men. Now I am the friend and brother, living in peace together under the flag of our country.”

— Two Moons, Northern Cheyenne

Have you visited Little Bighorn Battlefield? Share your reflections or tips in the comments below. Let’s honor the stories of both troopers and warriors who walked this sacred ground.